What Disturbs Our Blood is FitzGerald’s second book. He shook the establishment a few years ago when he unveiled the secrets of Canada’s upper crust in Old Boys: The Powerful Legacy of Upper Canada College. Sexual abuse led to charges and convictions of three former teachers, and launched a class action lawsuit against the college in 2002.

What Disturbs Our Blood is FitzGerald’s second book. He shook the establishment a few years ago when he unveiled the secrets of Canada’s upper crust in Old Boys: The Powerful Legacy of Upper Canada College. Sexual abuse led to charges and convictions of three former teachers, and launched a class action lawsuit against the college in 2002.

What strikes me on reading What Disturbs Our Blood is the depth of research FitzGerald did to reveal the sad truths of the lives of his grandfather and father, both renowned doctors. The book is a hard look at the FitzGerald male line, its strengths, its weaknesses and the mental illness that compelled these men to commit suicide. At a time when the world honoured and respected them for their accomplishments in developing life-altering advances for the public good, establishing world-famous Connaught Laboratories and monumental public health networks with international recognition, the two men eventually struggled with self-destructive behaviour.

Fitzgerald embarks on a journey of discovery, bent on understanding and thwarting a suicidal curse that afflicts the male generations before him.

FitzGerald is a capable storyteller. Not once does he trot out the facts without weaving them into the context of the times: 19th century Irish immigrants, small-town Ontario, determination to excel, development of world health initiatives in Canada, two devastating world wars, Depression Era, privileged educational opportunities, the Jazz Age and post-war booms.

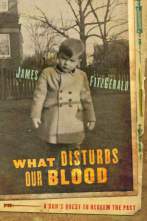

Tribute to Gerry FitzGerald (1882 – 1940)

Through generational time lines, the author shows a balanced view of where all went right, and where all went wrong. The author knew little about this mysterious grandfather. A family’s conspiracy to shroud his shameful death put out the flame of the man’s personal achievements and his achievements for Canada.

How can it be that men of such brilliance and vision, men on the front lines of miraculous public health cures that today we take for granted, and men associated with the best minds in psychiatry succumb to hellish depressions for which they see suicide as their only answer?

The author begins his book with his early remembrances of growing up in his grandfather-built home on north Toronto’s privileged Balmoral Street.

I was dipped in the lukewarm baptismal waters of Grace Church on-the-Hill, an austere High Anglican enclave of grey stone that gravely watched over neighbourig Bishop Strachan, the private girls’ school my sister was destined to enter: henceforth, the rituals of my young life would continue to mesh with these institutional vestiges of the Family Compact, the nineteenth century ruling class clique of the British colony of Upper Canada.

Author’s father’s descent into depression and eventual suicide:

… my father took more and more time off work. He was having a nervous breakdown, but we pretended not to notice. He cried to my mother that he was all washed up, that he could not handle his job any longer, and cancelled appointments with his patients. Only during my archival searchings decades later did I discover that he had been invited in June 1966 to attend the official opening of FitzGerald Building, a new laboratory facility on a three-hundred-acre property north of the city, honouring the memory of his illustrious father. Engulfed by a merciless malaise, he declined the invitation.

Author’s grandfather’s descent into depression and eventual suicide:

… Gerry rests at Connaught Farm, an unprecedented disruption of his long-standing work routine. He has spent his life deftly balancing work and holidays, recharging his body each summer to take a run at the busy fall term. But this fall, it’s as if a steady trickle of blood is leaking from the hull of a battered frigate, sapping his waning reserves of strength. He tries to keep himself occupied with rug weaving and other hobbies, but instead waves of apathy and agitation roll over him: each night, he swallows tablets of Nembutol to quell his insomnia. Edna handles his correspondence and postpones meetings.

The book is an insider’s look at Canada’s role in supplying a desperate world with preventative immunization against diptheria, smallpox, rabies, polio, diabetes, and allergies, a country becoming a world leader in inexpensive public health and quality controls.

But equally fascinating is a ramble through the early Freudian camp of psychiatry, which was opposed by leading doctors and suspicious non-believers in North America, choosing instead more invasive and ultimately more devastating treatments: Metrazol, lobotomy, insulin coma treatment and electric shock treatment. The North American model finally changed over from the early premise that insanity is associated with sin, or poor blood lines, which shamed the mentally ill to endure secretive denial, alienation and ineffective experimental brain and body cures that left many dazed and useless, or worse, dead.

The Who’s Who of modern medicine are characters in this book. Nobel prize-winners and decorated award winners push through their ideals to create institutions, universities, laboratories and international connections. But many of those brilliant strategists couldn’t benefit from the advances themselves. The book is peppered with famous suicides that quite frankly boggle the mind.

I highly recommend this book published by Random House Canada for its style, insights, historical significance and hope that the author brings to sufferers of mental illness.